Reconstructive Surgery After Treatment of Female Genital Tract Malignancies

Authors

INTRODUCTION

The prevailing treatment methods for some malignant diseases affecting the female genital tract are invasive to that body segment and in many instances result in compromise of physical function. Initial treatment planning for many years detailed the occurrence of morbidity and encouraged the acceptance of occasional residual physical deficit as sequelae for curative treatment of a dreaded disease. Advances in the delivery of cancer care led to a decrease in surgical morbidity, increased survival after surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, and greater life expectancy with a good quality of life. With these advances, contemporary treatment planning began to emphasize full and complete return to normal functioning of the patient and in particular the body segment undergoing reconstruction. The era of better informed consent with patient understanding of treatment options and outcome plays an important role in treatment planning and in the recovery process. Other reasons for emphasizing restoration to full functioning include the following:

- Increased longevity

- Increased attention to preservation of body image

- Maintenance and enhancement of physiologic activity

- Improvement in psychosocial well-being

Among current-day trends for reconstructive procedures on the female genital tract, underlying dogma include the following:

- Reconstruction should be performed at the time of surgery rather than after a recuperation period unless dictated by special circumstances.

- Early reconstruction accelerates the return to physical functioning. Better functional results are obtained.

- Techniques from other surgical disciplines are being incorporated into the treatment approach.

RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

The surgical techniques used in reconstructive procedures on the female genital tract range from simple procedures involving the application of split-thickness skin grafts to very complicated procedures in which large segments of skin and underlying tissue, including muscle, are used as flaps to cover gaping defects created at the time of radical or ultraradical surgery. These techniques include grafting procedures, realignment of standard incisions, the use of vascular pedicle flaps, and organ substitution.

These procedures can be further categorized as follows:

Grafting

Split-thickness skin graft

Simple

Extensive (skinning vulvectomy)

Full-thickness skin graft

Use of pelvic peritoneum as a graft

Realignment of Standard Incisions

Z-plasty

Rhomboid flap

Transposition flap

Vulvovaginoplasty

Use of Vascular Pedicle Flaps

Simple flaps

Labial pedicle flap (Martius flap)

Omental pedicle flap

Complicated flaps

Gracilis, rectus abdominis flaps

Tensor fascia latae flap

Gluteal, perineal, and thigh myocutaneous flaps

Organ Substitution

Transplantation of the bladder dome

Use of a segment of the sigmoid colon or ileum to create a new vagina

Creation of a urinary pouch

BASIC UNDERLYING SURGICAL PRINCIPLES

Certain basic principles are inherent in successful reconstruction:

- An effort should be made to preserve or enhance blood supply to the operative site.

- Meticulous hemostasis at the surgical site is critical.

- The use of fine suture material is mandatory.

- Suture lines should not be closed under tension.

- Gentle handling of tissue is essential.

- Dead spaces should be obliterated.

- All possible evidence of previous infection should have been removed.

Among the conditions that lead to complications when performing reconstructive procedures are: (1) decreased blood supply, (2) fibrosis at the operative site, (3) age (older patients have more problems), and (4) unrecognized infection. The aim of reconstruction should be to return the anatomic site to normal appearance and function.

VULVAR AND PERINEAL RECONSTRUCTION

Split-Thickness Skin Grafting

The establishment and easy applicability of split-thickness skin grafts have enhanced the gynecologists' role in reconstruction of the vulva. When wide local excision of vulvar lesions creates large defects, a segmental skin graft can be applied so that skin approximation without tension will ensure a better cosmetic result. Primary closure and segmental grafting can be used at the same surgical sitting.

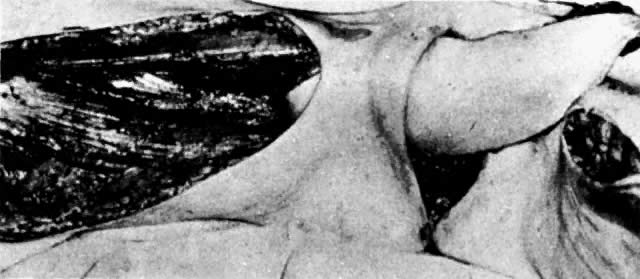

The presence of multifocal vulvar, perineal, and perianal lesions occasionally necessitates the removal of multiple areas of skin. Reapproximation is difficult. The technique of removing just the vulvar skin (i.e., skinning vulvectomy) and preserving the subcutaneous tissue and vulva blood supply is preferred.1 A rich bed of tissue is available for skin-graft applications (Fig. 1). Although operative time and hospital stay are lengthened when skinning vulvectomy and grafting are performed, better cosmetic results with few residual sequelae are obtained. Among these sequelae are graft-take failure in the range of 5% to 15% and an impairment of sensation in both the grafted area and the graft site. The mons pubis is a potential graft selection site.

Use of Incisions and Skin Grafts

Introital stenosis after surgery is not always responsive to dilation. Simple surgical procedures, such as vertical incisions at the fourchette, constitute a first approach. These incisions are closed in horizontal fashion to widen the introitus. In cases of introital stenosis or the absence of a perineal body, a Z-plasty type of operation can be performed.2 If larger areas of the vulva need to be covered after radical surgery, local flap grafts can be used.3,4

Use of the Labia Minora (Full-Thickness Graft)

Patients with prior vulvar surgery may experience complications such as dyspareunia, introital stenosis, hoods over the urethral orifice, vulvar scarring, and vulvar breakdown with infection. In these patients, vulvar reconstruction can be performed by using full-thickness grafts.5,6 Full-thickness grafts use both the epidermis and the dermis. In general, these grafts can be used to cover small areas so that the donor site can be closed primarily. For the gynecologists, possible donor sites include the labia minora,5 upper medial thigh, and groin.6 The size of the graft should be larger than the area to be covered secondary to the high primary contracture rate. The use of skin grafting at the time of initial vulvar surgery can circumvent many of the aforementioned complications.

Labial Pedicle Flap (Martius)

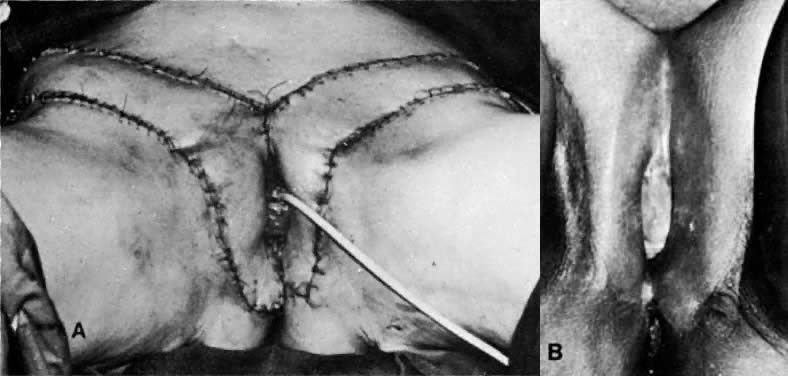

After radiation therapy, hypoxia, necrosis, and ulceration can compromise genital tract tissues. Conditions such as vesicovaginal, rectovaginal, and urethrovaginal fistulas can be the sequelae of pelvic irradiation. Repair of injured tissue in these areas necessitates the introduction of healthy unirradiated tissue. The closure of these defects can be approached with the use of the labial fat pad, a technique originally devised by Martius.7 The Martius procedure provides tissue support and a new blood supply to the surgical site. The labial fat pad is supplied anteriorly by the superior external pudendal artery and inferiorly by the perineal branch of the internal pudendal artery. As a labial pedicle, the bulbocavernosus muscle and surrounding fat is isolated. This pedicle is tunneled paravaginally and then introduced into the vaginal canal, where it can be used to repair bladder and urethral fistulas7,8,9 or rectovaginal fistulas.10,11 Both labial fat pads can be used (Figs. 2 and 3).

Rhomboid Flap

Creation of a rhomboid flap is a useful approach for repairing defects occurring after partial vulvectomy has been performed for carcinoma in situ of the vulva or re-excision of the vulva for in situ disease.12 The flaps are created such that a graft is not necessary and adequate closure without tension is obtained.13

VAGINAL RECONSTRUCTION

Vaginal reconstruction is critical for maintenance of sexual functioning, psychosocial health, restoration of body image, and for pelvic support to prevent bladder, rectal, and pelvic prolapse. Among the conditions leading to impairment of vaginal function are the following:

- Surgical removal of the upper vagina or the entire vagina at the time of conservative, radical, or ultraradical surgery

- Contraction, constriction, erosion, or ulceration of the vagina after irradiation for cervical, vaginal, or endometrial cancer

- Fistula formation

The technique of vaginal reconstruction depends on the length of the remaining vagina, the viability of the tissue, and the accompanying deficit as a result of the treatment method. Procedures that have been described include split-thickness and full-thickness skin grafts, peritoneal grafts, omental grafts, vulvovaginal grafts, large- and small-bowel grafts, bladder segment grafts, and myocutaneous flaps.

Split-Thickness Skin Grafting

In the absence of irradiation, vaginal reconstruction can be achieved by the placement of a split-thickness skin graft in the vaginal canal. Skin can be taken from the lower abdomen, the lateral hairless inguinal area, the posterior medial thigh, or the posterior medial buttocks. The graft usually varies from approximately 0.015 to 0.017 inches in thickness. Initially, split-thickness grafts contract approximately 20% compared with full-thickness grafts, which may contract up to 50%. However, the secondary contracture, which occurs as the wound heals, is much less for the thicker grafts. Therefore, thicker grafts are more pliable and contract less. The donor site usually heals without difficulty in 14 to 21 days; however, a residual scar will remain at the donor site. Graft-take ranges from 75% to 90%. This method of creating a neovagina can be used in patients who have had a partial or complete vaginectomy for intraepithelial or invasive carcinoma of the vagina or in patients who have had either an anterior or a total pelvic exenteration. When the latter is performed, creation of a vascular bed may be required; this can be created surgically with the use of an omental pedicle flap or muscle pedicle flap.

When using a split-thickness graft, a vaginal stent is necessary to keep the vagina patent. The stents are tailored to the size of the vagina. They should be easy to remove and should not remain in place for prolonged amounts of time. Excessive pressure should not be exerted on the graft as it can lead to vascular compromise and draft necrosis. After stent removal, topical estrogen can be used and the vaginal canal is kept open, either naturally or by the use of a mold. The mold is used for approximately 3 to 4 months if the patient is not sexually active; less time is required if the patient is sexually active.

Complications of vaginal reconstruction include loss of viability of the graft, stenosis of the vagina, and rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistula. Long-term complications of vaginal grafts include vaginal dryness, vaginal prolapse, and the rare development of squamous cell carcinoma of the graft.14 Thus, split-thickness skin grafts have emerged as one of the two more commonly used techniques for reconstruction of the female genital tract after treatment for gynecologic malignancies.

Use of Pelvic Peritoneum or Omentum

When the length of the vagina would be compromised at the time of radical or ultraradical surgery, intraoperative procedures can be used to lengthen the vagina. A simple procedure involves the use of pelvic peritoneum.15

Peritoneum from the vesicouterine pouch or from the cul-de-sac (extension of the peritoneum from the bladder and rectum) is preserved at the time of radical surgery and attached to anterior and posterior vaginal edges. The most superior or cephalad peritoneal edges are sutured in the midline. Thus, a peritoneal pouch that is an extension of the existing vaginal canal is created. Using this method, the vaginal depth can be extended by at least 2 to 3 cm (Fig. 4). In addition, omental pedicle16 or pelvic peritoneum15,17 can be used to cover the pelvic floor and the dome of the denuded vaginal canal. Approximately 3 to 6 weeks after surgery, after vaginal patency is maintained, a split-thickness skin graft can be applied to the vaginal tube.

Variation of Standard Incisions

VULVOVAGINOPLASTY.

The current-day procedures use either the basic technique or minor modifications of the original Abbe-McIndoe-Williams procedure.18 This procedure begins with an incision of the labia majora as outlined in Figure 5. The inner lateral edges of the incised skin are then approximated to create a tubular vagina (Fig. 6). This tube is interior to the reapproximated outside edges of the incision.

This technique allows the creation of a functional vagina in approximately 6 to 8 weeks. Advantages of this procedure are that dissection of the perineum is not necessary, the vagina retains its sensory function, routine dilation is not required, hospitalization is decreased, and the patient is able to ambulate early.

This procedure is exceedingly useful after vaginectomy or when shortening of the vaginal canal has occurred, such as after radical hysterectomy or vaginal irradiation, when the length of the vagina is compromised.

Among the complications of this operation are stenosis of the canal, prolapse of the vagina, and the rare occurrence of either rectovaginal or ileovaginal fistulas. A change in the direction of the vaginal canal occurs after surgery. In addition, the vaginal skin usually is dry, and lubrication is required before coitus. Occasionally, there is hair growth in the neovagina.

PERINEAL INCISION.

Another technique reported by Simmons and Millard19 and West and coworkers20 for creation of a vagina involves the dissection and creation of a new vagina between the compromised posterior vagina and the anterior rectum. This rare surgical procedure is used when there is severe vaginal stenosis secondary to irradiation. A vaginal pouch as large as 10 cm in length and 5 cm in width can be created and lined with a split-thickness skin graft. A vaginal mold and continued vaginal dilation are required to prevent scarring.

Organ Substitution

SEGMENT OF BOWEL.

In the past, the intestines have been used to fashion a vaginal tube. At the time of exploratory celiotomy, a vaginal tube can be created by using either a loop of ileum or a segment of the sigmoid colon.21 Preservation of the blood supply to the bowel segment is critical to the success of this operation. The segment is used either to fashion a neovagina entirely or to attach it to a vaginal remnant to augment vaginal length.

This method was popular with European surgeons but is rarely used today. It served as an impetus for the development of current-day techniques, because routine canal dilation and the use of stents were circumvented. Mucous secretion from either the ileum or the sigmoid, primarily the sigmoid, was bothersome to many patients.

USE OF THE BLADDER DOME.

A less-popular method for creation of a neovagina involves the use of the bladder dome.22 A segment of bladder is resected, the epithelium is removed, and this portion of the bladder is used to fashion an upper vagina. Usually, this procedure is followed by application of a split-thickness skin graft to fashion the lower vagina. This procedure is rarely used today.

USE OF A MYOCUTANEOUS FLAP.

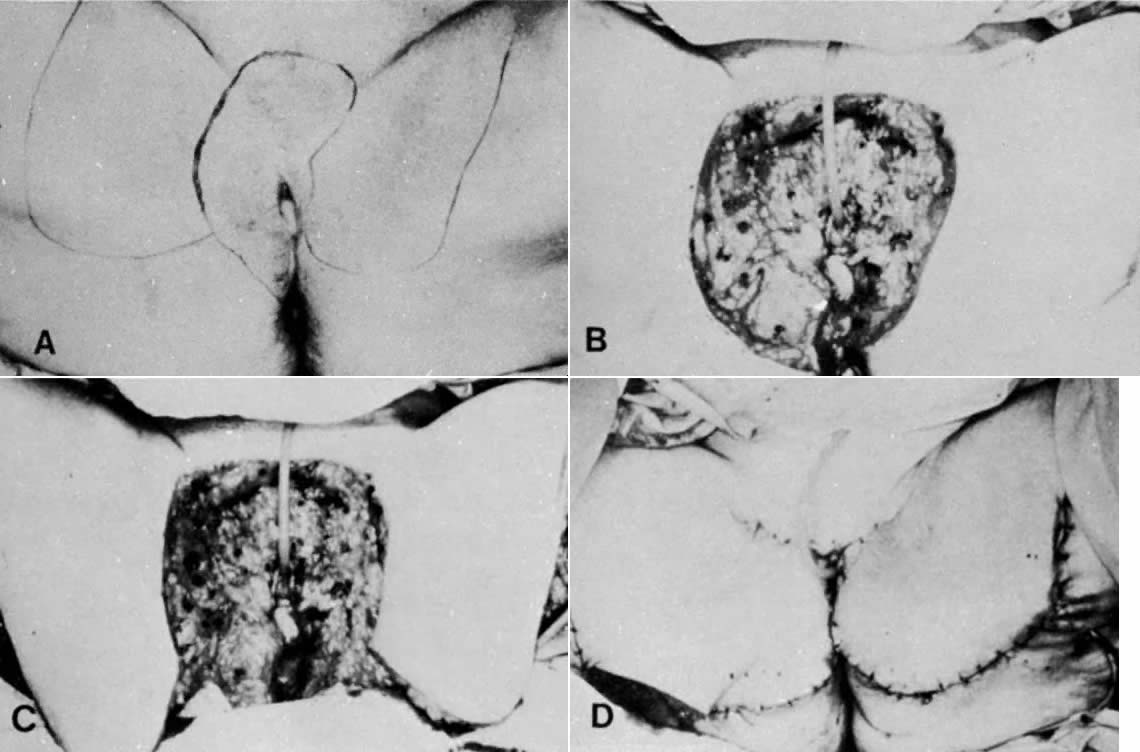

The presence of gaping defects in the pelvic-vaginal cavity after ultraradical surgery such as a total pelvic exenteration has necessitated the use of larger flaps. Myocutaneous flaps have enjoyed increasing popularity in these instances. One favorite technique involves using the gracilis muscle to close the pelvic defect and create an adequate vagina (Figs. 7–11). To reduce the bulk associated with this flap, a shortening of the flap with equally efficacious results has been recommended.23

Rectus abdominal muscle flaps have also been used for vaginal reconstruction. One advantage is that only a single flap is necessary, compared with two gracilis flaps, and, second, the donor site incision can be closed with the laparotomy incision in cases of exenterative procedures. Disadvantages of the rectus muscle flap include difficulty of stoma placement and that a two-team approach may no longer be possible.24,25

URINARY CONDUIT.

With the trend toward better cosmesis oncologists have attempted to enhance patient comfort and acceptance after radical surgery. One such advancement has been the creation of a continent urinary conduit. The large and small intestines are used to create a urinary reservoir intra-abdominally, and although an abdominal wall stoma still is present, there are several advantages for the patient. The stoma is smaller and the patient does not have to constantly wear a urinary receptacle. In addition, a low rectal anastomosis or anastomosis of the colon, rather than an end sigmoid colostomy, allows the patient to be free of a conduit for the stool. These two refinements significantly enhance the body image of the patient undergoing radical pelvic surgery.

RECONSTRUCTION OF LARGE DEFECTS

When large defects of the pelvis, vagina, vulva, groin, or perineum need closure, elaborate reconstructive techniques are used. The development of flaps with a single-muscle vascular pedicle was a hallmark achievement in reconstructive surgery. By covering large defects lacking subcutaneous tissue with muscle flaps, a better cosmetic result was obtained. Patients were able to ambulate earlier and recovery was accelerated. The presence of muscle in the flap decreased the infection rate and allowed the superficial skin to maintain better nutrition. Function is not impaired by mobilization of muscle flaps from donor sites.

Among the choices of myocutaneous flaps used to cover large defects are the rectus abdominis muscle24,25 used for pelvic or vaginal defects, the gracilis flap26,27,28 used for vaginal and pelvic defects, and the tensor fascia lata29 used for vulvar defects.

Among the complications of myocutaneous flap application are hematoma formation, peripheral tissue necrosis, decreased flap take, redundant flap skin, painful thigh scars, and leg hyperesthesia.

Gracilis Flap

The gracilis flap technique is described in many publications.26,27,28 Careful measurement of flap length before surgery is an important step when using this method of therapy. Usually, the flap should not be longer than 24 cm or wider than 7 cm. During surgery, the blood supply of the flap can be gauged by the intravenous injection of 10 mL of a 10% fluorescein solution (resorcinolphthalein).30 The flap is then inspected under a Wood's ultraviolet light. Spotty fluorescence of the skin and underlying tissue usually indicates an intact blood supply. The blood supply is from the medial femoral circumflex artery, a branch of the deep femoral artery. Groin, vulvar, perineal, and vaginal defects can be covered with this flap (Figs. 12 to 14). One disadvantage to the gracilis flap technique is that it requires two flaps to create a neovagina, and the incisions can be unacceptable to the patient. In addition, a rare gracilis flap complication is the occurrence of painful knees due to inclusion of the saphenous nerve when the gracilis muscle is reflected.

Tensor Fasciae Latae Flap

Would breakdown and infection occur in up to 50% of patients after radical vulvectomy and inguinal node dissection? The avoidance of primary closure and the introduction of myocutaneous grafting procedures have reduced the incidence of these two complications. In addition, postoperative morbidity has decreased and hospital stay has been reduced dramatically.

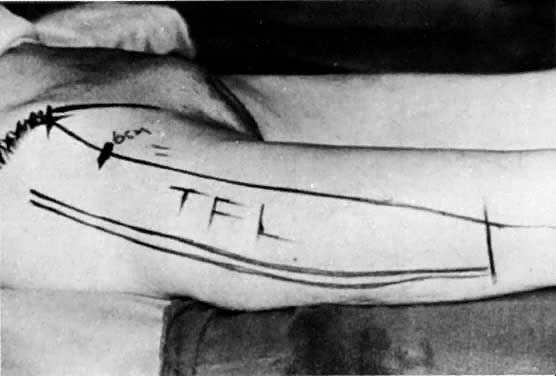

The tensor fasciae latae muscle lies between the gluteus medius and the sartorius muscle (Fig. 15). It has a singular vascular pedicle from the lateral circumflex femoral artery, which is a branch of the deep femoral artery. The muscle and its blood supply can cover a defect 40 cm in length and 15 cm in width. Superimposed skin is retained when this graft is used to close groin, vulvar, and perineal wounds (Figs. 16 and 17).

As mentioned, the tensor fasciae latae flaps have been used to cover inguinal defects at the time of radical vulvar surgery.29 Depression of the scar with bulging of the groins has been the main disadvantage of this flap. Other disadvantages include lateral instability of the knee, difficulty closing the incision, and the complications of myocutaneous flaps listed previously.

Gluteal, Perineal, and Thigh Flaps

These myocutaneous flaps are created from the buttocks, perineum, or thigh to cover gaping areas present after radical or ultraradical pelvic or vulvar and groin surgery.

These flaps can be substituted for gracilis or tensor fasciae latae flaps or be used in lieu of them. Additionally, the perineal flaps can be used as an adjunct to any of the other myocutaneous flaps. Use of the medial aspect of the thigh to create flaps to cover large denuded vulvar areas has been reported31 (Fig. 18). Abdominal-wall flaps, using the rectus muscle, are replacing some of these flaps.24,25

RECONSTRUCTION OF OTHER AREAS

Tumor invasion of the urethra and periurethral tissues may require resection of the distal urethra. Continence is often maintained when no more than the distal third of the urethra is resected; however, in some cases, reconstruction may be necessary. Neovascular tissue adds length to resected urethras and may be created from a variety of genital tissues, including periurethral tissues, labia minora, and anterior vaginal wall mucosa.32,33,34 All techniques involve mobilization of nearby healthy tissues to create a tubelike structure to augment the foreshortened urethra. Tightening of the urethral sphincter by placement of deep sutures at the urethrovesical junction also may be necessary depending on the degree of incontinence. Reports on the various techniques of urethral reconstruction have noted good results.

Perineal reconstruction may be required when extensive resection of the perineum and anal region has taken place. Gracilis muscle flaps have been used to reconstruct the perineum and correct anal incontinence.35 Musculocutaneous island flaps obtained from the groin also may be mobilized to repair perineal defects.36 In a case report of cloacal reconstruction, ischiocavernosus muscle flaps were mobilized to recreate a perineal body.37 A variety of musculocutaneous flaps have been used for repair of perineal defects with good outcome.

SUMMARY

New reconstructive techniques continue to be developed with the advancement of technology and increased understanding of wound healing. Patients previously handicapped not only by cancer but by disfiguring surgery can now have restoration of anatomy and function. As pelvic reconstructive techniques continue to undergo further refinements, gynecologic oncologists can continue to offer patients with cancer restorative surgery that allows them to pursue lives with good quality.

REFERENCES

Rutledge R, Sinclair M: Treatment of intraepithelial carcinoma of the vulva by skin excision and graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol 102: 806, 1968 |

|

Wilkinson EJ: Introital stenosis and Z-plasty. Obstet Gynecol 38: 638, 1971 |

|

Julian CG, Callison J, Woodruff JD: Plastic management of extensive vulvar defects. Obstet Gynecol 38: 193, 1971 |

|

Korlof B, Nylen B, Tillinger KG et al: Different methods of reconstruction after vulvectomies for cancer of the vulva. Acta Obstet Scand 54: 411, 1975 |

|

Trelford JD: The labia minora as a pedicle graft to cover the defect of simple vulvectomy: A new method. Gynecol Oncol 2: 482, 1974 |

|

Morley GW, Delancey JOL: Full-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty for treatment of the stenotic or foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol 77: 485, 1991 |

|

Martius H: Gynecological operations and their topographic-anatomic fundamentals, p 271. Chicago, Chicago Canterbury Press, 1939 |

|

Patil U, Waterhouse K, Laungani G: Management of eighteen difficult vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistulas with modified Ingelman-Sundberg and Martius Operations. J Urol 123: 653, 1980 |

|

Hoskins WJ, Park RC, Long R et al: Repair of urinary tract fistulas with bulbocavernous myocutaneous flaps. Obstet Gynecol 63: 588, 1984 |

|

White AJ, Buchsbaum HJ, Blythe JG et al: Use of the bulbocavernosus muscle (Martius procedure) for repair of radiation induced rectovaginal fistulas. Obstet Gynecol 60: 114, 1982 |

|

Elkins TE, Delancey JOL, McGuire EJ: The use of modified Martius graft as an adjunctive technique in vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula repair. Obstet Gynecol 75: 727, 1990 |

|

Lister GD, Gibson T: Closure of rhomboid skin defects: The flaps of Limberg and Duforermentel. Bost J Plast Surg 25: 300, 1972 |

|

Burke TW, Morris M, Levenback C et al: Closure of complex vulvar defects using local rhomboid flaps. Obstet Gynecol 84: 1043, 1994 |

|

Rotmensch J, Rosenshein N, Dillon M et al: Carcinoma arising in the neovagina: Case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol 61: 534, 1983 |

|

Saito M, Kumasaka T, Kato K et al: Vaginal repair in the radical operation for cervical carcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 55: 151, 1976 |

|

Franklin EW, Bostwick J, Burrell MO et al: Reconstructive techniques in radical pelvic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 129: 285, 1977 |

|

Morley GW, Lindenauer SM, Youngs D: Vaginal reconstruction following pelvic exenteration: Surgical and psychological considerations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166: 966, 1973 |

|

Williams EA: Congenital absence of the vagina: A simple operation for its relief. J Obstet Gynecol Br Commonw 71: 511, 1964 |

|

Simmons, RJ, Millard DR: Reconstruction of a functioning vagina following radiation therapy for cancer of the cervix. Surg Gynecol Obstet 112: 761, 1961 |

|

West JT, Ketcham AS, Smith RR: Vaginal reconstruction following pelvic exenteration or post radiation necrosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 118: 788, 1964 |

|

Pratt JH, Smith GR: Vaginal reconstruction with a sigmoid loop. Am J Obstet Gynecol 96: 31, 1966 |

|

Watring WC, Lagasse LD, Smith ML et al: Vaginal reconstruction following extensive treatment for pelvic cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 125: 809, 1976 |

|

Soper JT, Larson D, Hunter VJ: Short gracilis myocutaneous flaps for vulvovaginal reconstruction after radical pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 74: 823, 1989 |

|

Benson C, Soisson AP, Carlson J et al: Neovaginal reconstruction with a rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Obstet Gynecol 81: 871, 1993 |

|

Tobin GR, Day TG: Vaginal and pelvic reconstruction with distally based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 51: 62, 1988 |

|

Wheeless CR, McGibbon B, Dorsey JH et al: Gracilis myocutaneous flap in reconstruction of the vulva and female perineum. Obstet Gynecol 54: 97, 1979 |

|

Becker DW Jr, Massey FM, McGraw JB: Musculocutaneous flaps in reconstructive pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 54: 178, 1979 |

|

Burke TW, Morris M, Roh MS et al: Perineal reconstruction using single gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Gynecol Oncol 57: 221, 1995 |

|

Chafe W, Fowler WC, Walton LA et al: Radical vulvectomy using the tensor fasciae latae myocutaneous flap. Am J Obstet Gynecol 145: 207, 1985 |

|

McGraw JB, Myers B, Shanklin KD: The value of flourescein in predicting the viability of arterialized flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 60: 710, 1977 |

|

Hirshowitz B, Peretz B: Bilateral superomedial thigh flaps for primary reconstruction of the scrotum and vulva. Ann Plast Surg 8: 390, 1982 |

|

Hendren WH: Construction of female urethra from vaginal wall and perineal flap. J Urol 123: 657, 1980 |

|

Chambers JT, Schwartz PE: Mobilization of anterior vaginal wall and creation of a neourethral meatus after vulvectomies requiring resection of the distal part of the urethra. Surg Gynecol Oncol 164: 274, 1987 |

|

Mundy AR: A technique for total substitution of the lower urinary tract without the use of a prosthesis. Br J Urol 62: 334, 1988 |

|

Nowacki MP, Towpik E: Reconstruction of the anus, rectovaginal septum, and distal part of the vagina after post-irradiation necrosis. Dis Colon Rectum 31: 632, 1988 |

|

Ohtsuka J, Okaoka H, Saeki H et al: Island groin flap. Ann Plast Surg 15: 143, 1985 |

|

Elstein M: Cloacal reconstruction and use of bilateral ischiocavernosus muscle flap for construction of the perineal body. Case Report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 93: 402, 1986 |